Technology has made extremely broad distribution possible for political memoirs. Cheap ghostwriters are also easy to find. The Information Age has turned memoir from a mountain where a candidate might plant their flag for history to another critical channel for an electoral edge. That changes everything.

Historical Presidential Autobiographies

Early presidents occasionally wrote memoirs of their time in politics. Jefferson, Van Buren, and Buchanan were all excellent examples. Of their three books, two are essentially forgotten. Jefferson’s memoir, The Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson, is still widely read and rated on Goodreads. Van Buren’s autobiography, The Autobiography of Martin van Buren, was compiled from his papers after his death and never appeared to have wide readership outside of scholarly circles. Buchanan’s memoir, Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of Rebellion, was a bald attempt to defend his reputation in an era when people already considered him one of the worst presidents in history. The Complete Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant was probably the most successful of these among its contemporaries, although it hasn’t remained popular. Coolidge, Eisenhower, Hoover, and Truman all published memoirs after their presidencies. Coolidge, the famous Silent Cal, was even successful enough that he briefly became an advice columnist after the success of his serially published The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge. But it’s predictable that we’d encounter presidential autobiographies. Presidents have unique and noteworthy lives that are interesting to learn about. What’s surprising is how many more presidents have started to publish since 1950, and how the role of presidential autobiography has switched from retrospective to sales pitch.

The Presidential Bio Boom

Presidental bios have always been quite common, from Ida Tarbell’s The Early Life Of Abraham Lincoln to Ron Chernow’s Washington: A Life. Some of the best of these have been retrospectives, but many have been campaign PR tools, too. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s glowing biography of his Bowdoin classmate Franklin Pierce is one of the most infamous. It tanked Hawthorne’s respectability in New England literary circles and reduced him to a career of political cronyism. Teddy Roosevelt partially made his living as a writer after going broke in 1886. He was the first President to write an autobiography prior to his campaign. In 1898, he’d resigned as Secretary of the Navy and formed a ragtag band of elite fighters, with whom he fought in Cuba. His account of that time, The Rough Riders, was a tale of derring-do and over-the-top manliness. There is no way that voters could have ignored it. Roosevelt won office two years later. The Rough Riders still has over 2,600 ratings on Goodreads. Presidential memoirs that were published in the first half of the 20th century were mainly retrospective. Roosevelt himself wrote another autobiography, and Calvin Coolidge penned his book during that time too. A Presidential candidate wouldn’t pre-game their election with an autobiography again until Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Getting Elected With Autobiographies

Sixteen of the 38 existing presidential autobiographies have been about the candidates’ lives outside of the presidency. Considering that fact, it’s impressive that 12 of these could possibly have influenced the public’s perception of the candidate prior to election. These were essentially active players on the political field. Intentional or otherwise, they must have influenced how voters saw presidential candidates. As a result, they’re now becoming obligatory. Of the last seven presidents, six had already published memoirs prior to coming into office. Carter, the two Bushes, and Obama appear to have done so conscious of the fact that they would run for office. (Donald Trump published Crippled America while campaigning in 2015, but calling this an autobiography is a stretch.) But the first modern ventures into mass influence via autobiography appear to have been accidental. When Eisenhower wrote Crusade in Europe in 1948, four years prior to his election as president, he claimed that he had no interest in running for office. In fact, at the time that he wrote this book, Eisenhower was very much against the election of any military man for president of the U.S. He resisted overwhelming support for an Eisenhower run and instead left politics to become president of Columbia University.

Eisenhower’s Success

While it’s not impossible that his book was politically ambitious in the academic arena, it doesn’t seem to have been an attempt to win presidential office. Eisenhower almost certainly wasn’t trying to bend the public’s mind toward the idea that he’d be a good commander in chief. Nevertheless, bend it he did. The book cemented Eisenhower, already a famous general, as a household name and an example of an honorable, intelligent man. It also made him a ton of money; the future President received an advance of over $600,000, which would be worth over $6.4 million today. This was a sum so large that Eisenhower had newsworthy legal trouble over it. Obviously Eisenhower either ended up changing his plans or dropping a truly excellent bluff. He ran for president in 1951, winning office, and published a more traditional presidential memoir two years after leaving in 1963. His books may not have been meant to raise his profile, but they almost certainly influenced his election. Later politicians appear to have taken note of this fact; before Eisenhower’s term was out, Nixon and Kennedy had both decided to borrow his strategy.

Nixon Goes To The Publisher’s Office

Kennedy didn’t write an autobiography. Instead, he wrote Profiles in Courage, still a popular book that was written by a ghostwriter with the express purpose of showing the nation what mattered to JFK. The experience was hugely valuable. It established Kennedy as a media-savvy politician who was in tune with the best of American values. This information would come in very handy when Kennedy advised Richard Nixon to write a memoir. Nixon’s 1962 autobiography, Six Crises, detailed several of his great political successes. It was also a direct response to John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage, written at the urging of the newly installed President Kennedy himself. Anyone would have assessed Nixon as being in dire need of some good advice at the time. Tricky Dick’s political career was at a low point. He’d lost against Kennedy in the 1960 Presidential election, and then he’d also lost a bid for the governorship of California. After that defeat, he’d stalked off in a highly public and televised fit of pique and self-pity. He remained ambitious, but his image needed rehabilitation. Whether Kennedy told him to brag about himself for 480 pages is anyone’s guess. Nevertheless, this strategy worked. Nixon’s mediocre memoir became a hit, selling 300,000 copies despite the fact that it wasn’t very good. Part of the reason for this might have been that few other politicians had ever gotten as gossipy, personal, or insider-y as Nixon. The book threw shade on people who were concurrently active in politics and explained, in detail, why Nixon was better than them. It didn’t need to have artistic merit.

A Change Of Approach

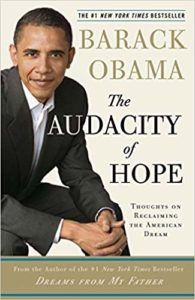

Nixon’s book writing strategy tells you something important about the man. Kennedy published a book about impressive politicians who were not himself, and in response, Nixon wrote a book quacking about how great Nixon was. Like Kennedy, he used a ghostwriter. (He did manage to pen one entire chapter by himself.) Despite the self-centeredness and general low quality of Nixon’s memoir, it succeeded in raising his profile. The next time Nixon ran for President, he won. In retrospect, it is hard to imagine a less stable or appropriate candidate. (Alas, it is no longer impossible.) But Nixon the man wasn’t who America elected. People voted for the politician they’d read about in Six Crises. After Nixon’s campaign memoir, candidates increasingly pre-gamed their campaigns by publishing books. Carter published Why Not The Best? The First Fifty Years two years before he was inaugurated, and George H.W. Bush published Looking Forward in 1987, four years prior to the 1991 completion of his campaign. However, the benchmark candidate autobiography was The Audacity of Hope. Barack Obama’s campaign memoir has been, to date, the most successful pre-Presidential book ever written. It may well be one of the most successful Presidential autobiographies, period. With an advance of $1.9 million, the then little-known Midwestern politician managed to present himself to the nation, lay out his plans for the Presidency, and remain on the New York Times Bestseller List for 30 weeks. There’s no question that this 2006 book affected Obama’s 2008 election. It was an international hit, a Grammy winner, and a validation of the fact that Presidents needed to tell their stories to win elections.

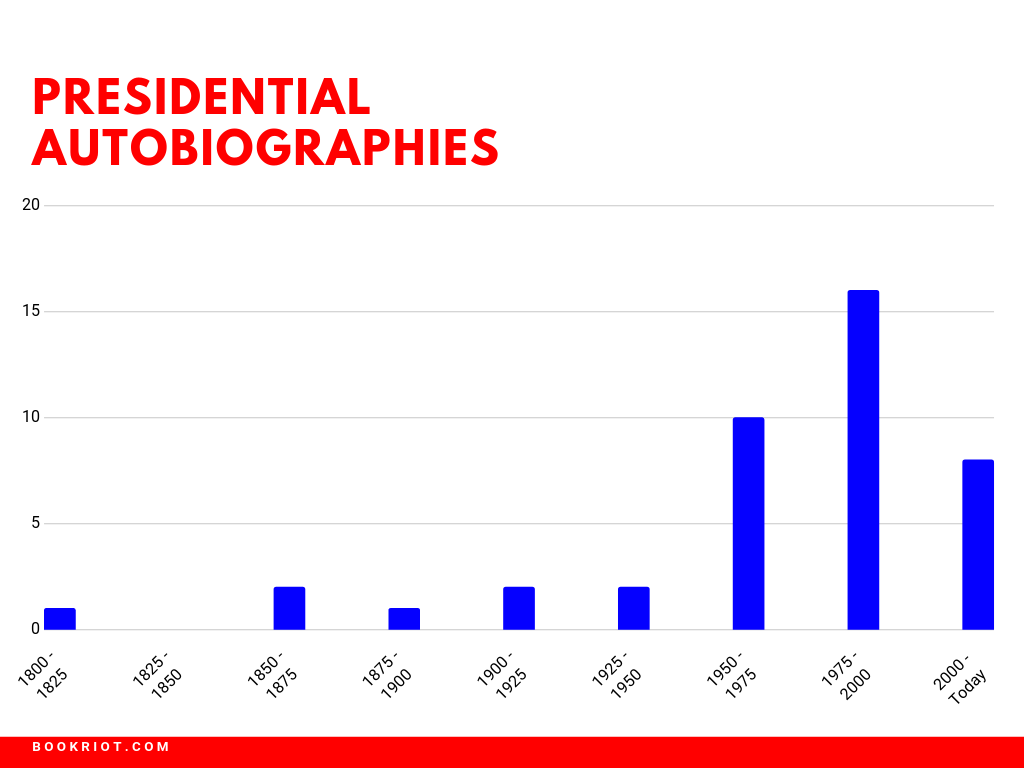

An Increasing Rate Of Publication

Eighteen out of our 45 past leaders have written presidential autobiographies, although nearly all former presidents have had their speeches and diaries published. Of the 18 presidents who published, only three wrote books before 1900. Aside from Teddy Roosevelt’s The Rough Riders, the others were published well after the authors had retired from politics. (Or, in Van Buren’s case, died.) It wasn’t until after 1950 that the rate of presidential autobiography publication really began to skyrocket. Richard Nixon wrote two more autobiographies between 1975 and 2000, as did George H.W. Bush. Donald Trump padded out the number significantly, if unwittingly, by publishing three memoirs during this same time.

The Trump effect presents an odd conundrum to this list. As far as success goes, few presidential autobiographies have been more widely known. The Art Of The Deal stayed on the New York Times Bestseller List for 48 weeks in 1987, 13 of those in the #1 spot. Trump’s presidential candidacy gave it a late surge of popularity. However, since its publication, Trump’s ghostwriter, Tony Schwartz, has claimed that the book is largely fabrication. The fact that Trump was experiencing massive personal financial problems simultaneous to the publication of this blowhard memoir does undermine it, and as a result, the book has drawn a great deal of criticism. The success of his fallacious books may be analyzed as a version of Trump’s political career writ small. Critically speaking, his books are schlock at best. At worst, they are steaming piles of lies and egotism that present bad advice and encourage their readers to believe stupid things. However, their popular success has undeniably made money for their author.

Success and its Many Definitions

In the case of Donald Trump, the financial success of his autobiographies are probably something of a raison d’être. Jimmy Carter’s many autobiographies, most of which have spent time on the NYT Bestsellers list, may be a combination of income source and method for maintaining a role in American political thought. Aside from their growing role as campaign tools, the purpose of presidential autobiographies has historically been to inform posterity. Nixon, for example, departed from the confidence of Six Crises to defend his actions as President in RN: The Memoirs Of Richard Nixon. Similarly, Buchanan’s autobiography was a miserable attempt to re-describe a miserable Presidency. History tells us of one case in which money was a significant factor in the creation and popularity of a Presidential autobiography. Dying of throat cancer in 1855, Ulysses Grant pushed his deteriorating body to the limit to finish his swan song, The Complete Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. The book didn’t linger on Grant’s unimpressive Presidency. Instead, it emphasized his exciting war years and salad days as a national hero. Mark Twain published it. Grant’s memoir hit the stands just days before he finally succumbed to his illness. It was a smash hit. Grant’s widow, Julia, would be the beneficiary of about $450,000 in royalties. That’s the equivalent of over $12.5 million today. In an era when women without husbands were often in dire financial straits, this money could have meant more than just a small comfort to Grant’s bereaved wife.

Bestsellers

Most modern Presidential memoirs end up on the New York Times Bestseller List at least briefly. Campaign bios can’t necessarily match this; there are too many candidates for them to all become hit authors, and anyway, most of them won’t gain the Oval Office. However, every ex-president is automatically a subject of public interest. Presidential autobiographies net large advances and sell many copies. Simon and Schuster reportedly ordered an initial run of 200,000 copies for Richard Nixon’s 1990 memoir In The Arena, and George W. Bush netted $7 million for the first 1.5 million copies of Decision Points sold. (Incidentally, he began writing this book the day after he left office. What an impressive work ethic.) Exact sales figures can be hard to come by. Many books, like Clinton’s My Life, tell us something about their success by remaining on the New York Times Bestseller List for weeks or months. Others say more about themselves by not doing so. Gerald Ford’s A Time To Heal appears to have been one of those. Foreign Affairs described it as unpretentious, uncomplicated, and unruffled. Historically, it has barely left a ripple.

Importance

We’ve come to expect autobiographies from our presidents. We rake the coals of those who left us nothing and greedily ingest the drabbest of memoirs by those who did, even when their authors produced miserable or unremarkable administrations. Ford’s forgettable A Time To Heal has over 130 ratings on Goodreads. (Richard Nixon’s RN: The Memoirs Of Richard Nixon has over 800, The Art Of The Deal has over 14,000, and The Audacity of Hope has over 128,000.) Once upon a time, writing books was labor-intensive. Politicians reserved their presidential autobiographies for the ends of their careers. They wanted to impress history with a profound one-shot that cemented their presence in office as having been important. Now, would-be presidents want to impress the public ahead of their wins and foreshadow political greatness. At the same time, ghostwriters have become cheap. Publishing companies have caught on to the idea that pre-election memoirs are good business. Rolling the dice on certain charismatic candidates is a good bet. Mitt Romney’s No Apology led the New York Times Bestsellers List for one week in 2010, and Sarah Palin received an advance of about $1.25 million for Going Rogue. Presidential autobiographies are now part of a political scene that mirrors the entertainment industry, from all-day televised drama on cable news to copy sales and huge advances. There’s no coming back from that. Historians may one day pore over The Audacity Of Hope side by side with Six Crises and A Charge To Keep. But they may as well compare what we’ve come to expect of our Presidents with what they’ve been willing to provide. You want books about Donald Trump? Really? Sigh. Fine. If you’re more interested in looking toward the future, check out what the 2020 Democratic candidates are reading!